The Christmas season is the preferred time of the year for nostalgia, but for me it is Holy Week that best provides an excuse to look back on the years. Nostalgia is always something bittersweet at best, and the painfulness of harkening back is made easier by the darkness of the post-solstice world and the desolation of winter, contrasted against the glow of Yuletide, which makes all Christmases blend together in the glow of warm fire. In contrast, the reflections that arise at Holy Week are cast in the light of fast-moving springtime, of senses chilled by cold and fasting yet happily hoping for warmth. The scenes are much easier to remember.

Five years ago were the lockdowns. For a vast majority of the readers the pathetic and ignoble year of 2020 was likely one that denied them right worship. Our one-world expertocracy had shut down most of civil society, and the Catholic bishops of the world humbly kept their necks in the secular halter, shuttering churches and halting masses. This happened about St. Patrick’s Day 2020, if memory serves—right on the day of our schola practice—and so the last weeks of Lent were liturgically canceled. No Passiontide, no Easter Week, and not until Pentecost did some dioceses begin to allow a regular schedule of masses to return.

Winter had ended fairly early in my neck of the words, and the gray sterility of spring lasted longer than Lent. I was still single at the time, my work was still paused (though not the paychecks), there was literally nothing to do but buy liquor, and Easter looked to be a pretty dire time.

A priest friend of ours was now barred from offering public masses in his parish. I had gotten to know him because he offered the Traditional Mass on First Saturdays, a fact that was still semi-secret at the time (a change in bishops meant that his diocese is one of the few where the Latin Mass is doing better than before Traditionis Custodes, but I’ll refrain from saying more lest some hounds from the Vatican close in). Freed from any other obligations, he proposed that he and some mutual comrades offer the Easter Triduum at his parish. He was adept at offering the Latin Mass, but had never done much more than a high mass on a feria. I had been blessed to help offer pre-1955 observances at an FSSP parish as part of the schola, and knew the ropes. Another friend was an expert MC who from book-learning could rival Gueranger, and a third was less expert but could provide assistance at the altar. It would be a ragtag crew at his tiny smalltown church, but our small group of TLM aficionados could take some solace in knowing that high masses were being offered somewhere in the diocese.

We made our way to town. It was one that can be traversed in the time it takes to smoke an American Spirit. The appeal of such places is all the clearer when the vestiges of winter are still around you. The bitter wind is so strong you’re surprised it doesn’t blow the entire town away, and the frozen dirt in the fields reminds you just how dead you’d be if you found your way out on the trails between this town and the nearest town of 200 people, over twenty miles away. It is one of those blessed small towns that was basically forgotten by the most pernicious reforms of the Civil Rights era. No one ever cared enough to make it ghastly in the modern style; the worst housing it has are some split-levels from the 70s, and its decay was mitigated by the existence of the one shiny building in town, a health clinic. The town still had a pay phone, which I tried to use to call my mother on Easter. The operator said the call would cost seven bucks—and you wonder why no one uses these things anymore?

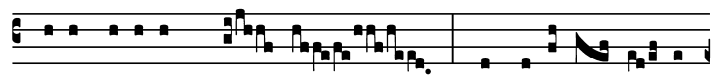

We began with Holy Thursday, that evening. The most striking feature was transferring the Eucharist to the altar of repose. We began the office of Tenebrae afterwards. Matins and Lauds are typically morning endeavors, but tradition (at least before 1955) moved them to the night preceding. In total, fourteen psalms will be sung and the Benedictus, along with nine readings and responses. Three of these are from the Lamentations of Jeremias. The Divine Office is a kind of undercurrent flowing beneath the masses, unseen by most laymen. Isaias spans Advent, the world begins again in Genesis at the start of Septuagesima, the Maccabees follow the very martial month of October. Jeremias gives voice to the pains of our Lord betrayed, and unites the sins of Israel with the consummate act of betrayal. Jerusalem, Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum. The special office of Tenebrae ends with participants on the ground, reciting Psalm 50 a second time, then pounding on the floor with books or fists. I think I’ve heard once from a learned source that the strepitus calls to mind the harrowing of Hell, but no learned source is necessary to conure relation to the infernal. After two hours of somber and despairing in darkness, one feels in proximity to Hell, the emptiness of death. The liturgical changes of 1955 were more disastrous to the Divine Office than the mass. Pius the Twelfth went so far as to change the text of the psalms; Pope John did us the benefit of changing them back. The nightly office of Tenebrae was truncated, with Vespers and Compline getting tossed alongside the perfidious Jews.

The onerousness of the old liturgical offerings puts the true sacrificial nature of the priesthood in perspective. Modern obsession with the vernacular has turned every reading at mass and hours into an opportunity for education, like a speaker addressing a town hall. Of course there’s no reason anyone can’t understand Latin, and for college educated people there’s no excuse for ignorance in this regard. In a society that boasts of universal literacy, looking down at a bilingual missal is now an act of insult. The act of chanting Matins and Lauds in a streak shows the start difference between offering as an act (offerens) versus offering as the thing offered (oblatus). A great harm of the Novus Ordo is the deemphasis of act and a fetishizing of words, a shift from the concrete to the intellectual. For all the conceits of traditionalists, Pope Paul’s mass is actually a far snootier thing than the old rite ever was. Every young Catholic who vociferously defends the Novus Ordo is a theologian or, worse than that, a canon lawyer. To defend its parity with the old rite requires theorizings that would make Kant go numb. As is often the case, being a fool sets one nearer the truth.

There are times when you long for the old rites and the old ways. An old townsman came in on Good Friday and interrupted the liturgy, because he wanted a particular prayer book. Some laymen get too chummy with priests, but this was worse than you’d treat a chum. Any bowing Buddhist or jabbering Turk would’ve likely earned some reverence from him, but the scene was familiar enough to warrant only contempt. The Improprium of Good Friday is, musically, the climax of the liturgical year, and as such is one of the heights of Western culture. You can never sing it well enough.

Holy Saturday is the longest liturgy of the year. We had chosen the Bugninified liturgy of post-55, meaning twelve readings had been sliced down to four, and the Office was no longer the same. The 1955 changes are mars on the face of the liturgy, and it is always an affront to read about their “newly restored” character in your Angelus Press missal. Even one unacquainted with the background can notice the changes; they are something inorganic and weird. A blessing that comes with this recognition is that the Novus Ordo Holy Week is less offensive in comparison. As a friend of mine commented, the Novus Ordo Holy Saturday liturgy restored some of the components stripped in ‘55. There is a repeated phrase on Holy Saturday that is the most haunting in all of Gregorian chant. It is hopeful, reaching high in odd interval, resolving in the decline of a full step, and continuing in a rapid and eerie manner. It seems a response to the mournful and similar phrase repeated often on the Good Friday. You find it also in the old Pentecost vigil and Septuagesima. It is another phrase you can never sing well enough.

We had a great feast after the Vigil mass. The reverent ladies wanted to show their appreciation for our work. Microwave dinners would have been fine.

On Easter morning another friend from the closest metropolis joined us (if I told you what metropolis it was, even the Omahans would laugh). The priest offered a sermon to the pews, which were empty. “This may be the only time in my priesthood I ever get to offer the traditional Triduum.” It was sad to hear. Though since that time I haven’t been able to participate in a complete Triduum either, and I don’t have any parishes in my care, just kids and a wife that make the necessary hours of travel unfeasible. The coronadoom hadn’t yet grown tedious at that point. One member of our TLM community died from it, and my priest friend would have suffered the same fate had not his bishop shown up and forbidden him to die. The actual lockdowns were in the early days actually quite fun, when the world was like a child’s empty playset. There was freedom there, if you had the guts to enjoy it. Every year since has been much less free, to the apparent satisfaction of most. It’s difficult to avoid crankery and conclude that the world is getting ineluctably worse, but the pleasure of getting old is the memory of the good.

I'm looking for a Catholic church currently and my big issue is my total contempt for most of the priests I encounter. I will never forget the cowardice of the church during COVID and it only takes a couple keystrokes to find out that any given church succumbed to the fear and panic of 2020 when I myself did not. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Russian Orthodoxy…